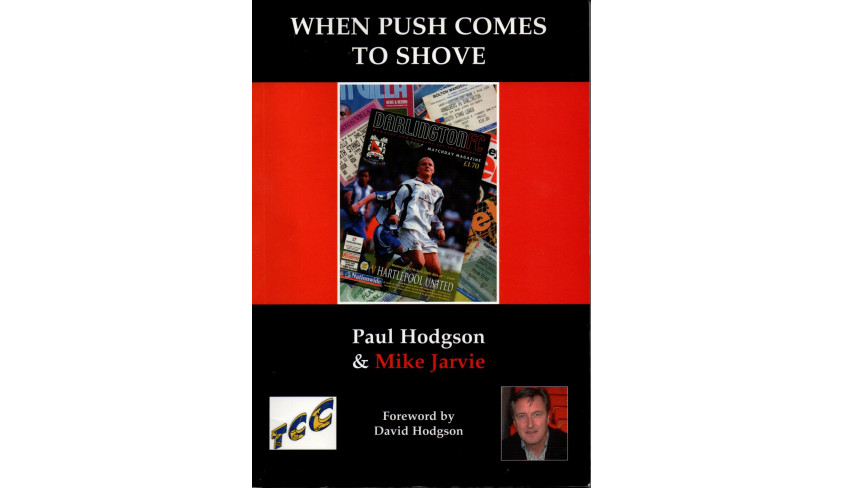

When Push comes to Shove

By Ray Simpson

Paul Hodgson's book on the official DFC website

One of Darlington's most loyal supporters, Paul Hodgson, wrote a book "When Push comes to Shove" some years ago about his experiences following Darlington FC.

Paul has now given us permission to publish the book on our website for the next few weeks -- we'd like to thank him for that.

To set the scene (as with all good books), Paul starts with the introduction:

Enjoy -- it's a great read, and something do while you're self-isolating!

The seeds for the present book were sown on 2 May 1998 by my co-author, Mike Jarvie. It was on this day that my friend David Robinson (alias Robbo) took Mike and me in his car to see Horden Colliery Welfare play Prudhoe Town in the last match of the season in the Second Division of the Arnott Insurance Northern League.

Although I had known Robbo since 1990, Mike had become a friend quite recently as a result of our collaboration on my autobiography, Flipper’s Side. We had begun work on that book the previous year and had already completed a first draft. Our trip to Horden therefore represented a break from the creative process, or so we thought.

Darlo were playing their last match of the season that day, away from home at Cardiff City, a game that in the context of the season as a whole meant next to nothing, which is why I reluctantly decided to give it a miss. Mike and I therefore glanced at the fixture list in The Northern Echo and picked a non-league match from our region instead. Another reason why we chose that particular game was because my old mate Steve Tupling, who used to play for Darlo in the 1980s, was turning out for Prudhoe Town.

Horden is one of those typical colliery villages you can find almost anywhere in the North East of England, with rows of former pit houses overlooking the grey North Sea. When we saw four skeletal floodlights poking above the rooftops, we made our way towards them through some meandering back streets until we arrived at the so-called Welfare Ground, which was adjacent to a cricket pitch.

We arrived at about twenty to three so we parked up and went for a drink in the Horden Big Club, which overlooked the ground. Although a notice on the door said that a club member must sign in any guests, we managed to gain admittance without any problem, and since the club was virtually empty Robbo challenged Mike to a game of snooker.

After we bought our drinks, Robbo paid the barman a £5 deposit for the table and put a twenty pence piece in the slot meter for the overhead light while Mike hunted high and low for two serviceable cues, but all he could find were two stumpy pool cues with worn down tips. Predictably, there was no chalk to be had either. Not that this would have improved their performance on the snooker table to any great degree I hasten to add!

While “Rocket” Robbo was racking up the balls, I asked “Meteor” Mike to put two pound coins in the bandit for me, which I managed to lose in record time. When it comes to fruit machines, I just never seem to learn, though maybe this eternal optimism can be traced back to my support for the Quakers. Always hoping for a win, more often than not I tend to be let down rather badly.

This proved to be the case only a few minutes later when someone wandered over to the bandit and almost immediately hit the jackpot. I therefore had to sit there and endure the sickening sound as £200 in pound coins spewed from the machine.

While I supped my pint of lager, I watched the snooker, which I must admit was dire. Robbo and Mike both played rubbish, giving away fouls like nobody’s business, until the very end, that is, when Mike somehow managed to pot brown, blue, pink and black, which ensured that he won the frame. By this time it was a quarter past three.

Leaving the club, we made our way to the ground to learn that Steve Tupling had already scored for the visitors and that the two sides were drawing 1-1. We paid our modest entrance fee of £1.50 each, but there were no programmes or team sheets available, not that I was particularly bothered by this stage. Our presence now meant that the “crowd” had swelled to number some eighteen souls.

As we surveyed our surroundings, Mike pointed out the coils of razor wire behind the main stand – though whether this was to stop people climbing in or getting out was a moot point. To add to the sense of dereliction, weeds were flourishing in every nook and cranny of the crumbling terraces.

I noticed a blackboard marked “Canteen,” so I asked Mike to push me through the entrance, underneath the main stand, so I could get a cup of coffee. On our way we passed yet anoth-er blackboard with a menu written on it, and a table with bottles of tomato ketchup, a bowl of sugar, a plastic container of salt and some greasy leftover chips in a polystyrene tray.

Beyond the flap of the counter, you could see steam billow-ing up from a chip pan on the electric cooker, and higher up there was a microwave oven. Sitting on a shelf was a black and white portable television set, its grainy monochrome picture showing a rugby match. Since the ball was the wrong shape, neither of us bothered watching it.

The canteen was like looking through a wall into some-one’s kitchen. In one corner there was a big bag of spuds on the floor. Instead of getting a disposable plastic cup I even got a proper mug of coffee for my fifty pence. Someone in the queue then made the mistake of asking for a burger, but the man behind the counter said they were right out of them until next season!

At half time Robbo disappeared inside his car to listen to the match report from Cardiff – one of Steve Tupling’s former clubs, as I reminded Mike. During the interval, I took the opportunity of asking Mike to push me to the toilet, where we noticed some large planks of wood blocking off the solitary cubicle, so when I’d finished I emptied my plastic bottle down the urinal instead. Optimistically, I asked Mike if there was somewhere I could rinse my bottle. Not surprisingly, there wasn’t a sink of any description, but what did I expect for God’s sake, a marble basin with gold-plated taps? “Remind me to wash it later,” I said.

To amuse myself during the second half, I tried to wind up the Horden manager, who was standing near me on the touch-line, but he just wouldn’t rise to the bait. Since he was quite a tough nut to crack, I kept making sly digs at his team, and when one of the Horden players was lying injured on the ground I urged the referee to penalise him for time-wasting. Then, when the referee booked the Horden physio for swear-ing at him, I applauded the decision, which was going a bit far. Therefore, at the end of the match, which finished 4-3 to the home team, I had the good sense to apologise to the locals for my behaviour and shook hands all round.

We then went back to the car and heard that Darlo had drawn 0-0 with the Bluebirds. Another uneventful season had come to a close. We had finished in nineteenth position, or sixth from bottom, depending on how you look at it!

After the game, the three of us met Steve Tupling for a drink in the Horden Big Club where he told us that he’d ended the season having scored an impressive twenty-six goals from right fullback and midfield. He went on to explain that he was also working for the Probation Service, had just completed a sports degree and was about to take up a teaching post in Sep-tember at Whitley Bay High School, so he seemed to be get-ting on well with his life after being a professional footballer.

That visit to Horden provided a salutary lesson on what conditions are really like near the bottom of the Football League pyramid for a club scraping by with only meagre resources. Although Darlington is hardly the most glamorous side in the Nationwide Football League, this visit to Horden was literally the pits. In footballing terms it was a real eye-opener to see how the other half lives.

On the back seat of the car I’d left behind a copy of Kicking in the Wind by Derick Allsop. The book chronicles a year in the life of Rochdale Football Club and had been recommended to me by a friend. As we drove back to Darlington, Mike idly leaf-ed through this book and an idea began to form in his mind.

After Robbo had dropped the two of us off at my flat, Mike returned to the subject of our conversation in the car. Maybe, he explained to me, we could write a similar work, after we had finished Flipper’s Side, a book that would incorporate a season in the life of Darlington FC. To do the job properly, he said, we would have to take notes after every game, home and away.

This was only the second away game that Mike had been to with me – the first had been the derby match with Hartle-pool United in February 1998 (a pulsating 2-2 draw) but as Mike said, whenever I travelled to football matches the events that unfolded were hardly ever dull. The games that I had recalled in Flipper’s Side were evidence for that and Horden had been quite an entertaining adventure in itself.

In his words, I acted like a catalyst. Put me on a train, in a crowded pub or at a football match, and events would sudden-ly explode into life around me. My wheelchair, far from being an insignificant prop in my adventures, became a magnet, drawing to me all sorts of weird and wonderful people. The more that Mike spoke, the more I realised he was right.

Although it would make sense to write the book from one point of view, it would be based upon the impressions of the two of us. So this is how the book you are currently reading came into existence, although little did we know that our enterprise would eventually embrace two seasons, which were some of the most remarkable in the history of the club.